Dickinson on the Pleasure of Solitude

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you Nobody too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don't tell! they'd advertise you know!How dreary to be Somebody!

How public, like a Frog,

To tell one’s name the livelong June

To an admiring Bog!

I spoke at length about discovering Emily Dickinson as a young man last week, but I realized that I forgot the most embarrassing part: I quoted the first two lines of the above poem in my senior yearbook. If that’s not making you cringe, you’re not picturing the pony-tailed teenager in his cap and gown above the quote. That’s a deep dark secret, people.

I’ll try to redeem myself. What I liked about this, although I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, was its rejection of all of the trappings of high school cliqueness, a championing of inwardness. What does it mean to be “Nobody?” She gives us a hint in eschewing being “Somebody” with the disappointed “How public!” And it is the eyes of the watching public through which Dickinson feels blessedly anonymous.

Like Nichole, I have always been perfectly comfortable being sociable; but as an introvert, I recharge alone. To this day, we both end a fine evening of company with a satisfied sigh and an hour of silent co-reading. You’d think we despise each other, until one of us eventually pops up and says “hi!” to the other, batteries recharged.

Emily Dickinson didn’t have such a companion, and so invented one in herself. Several of her poems address this intense self-reflection, one of which is a favorite of mine now, and concludes my illustrated book of her poetry:

There is a solitude of space

A solitude of sea

A solitude of death, but these

Society shall be

Compared with that profounder site

That polar privacy

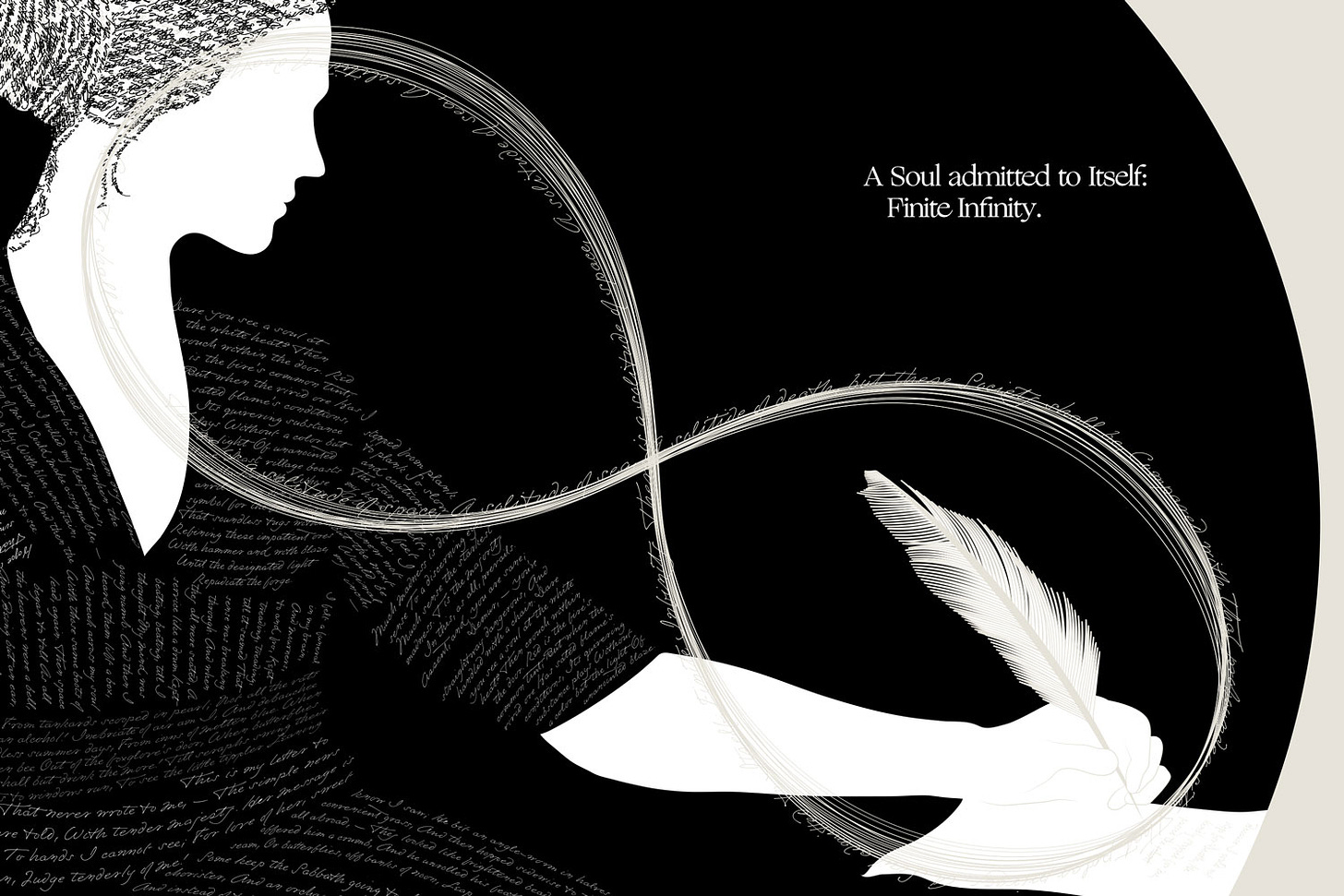

A soul admitted to itself–

Finite Infinity.

After I graduated the admiring bog of high school and went to college, I found this very similar passage from Shakespeare’s Richard II (Act V, sc. v):

My brain I’ll prove the female to my soul,

My soul the father, and these two beget

A generation of still-breeding thoughts,

And these same thoughts people this little world,

In humours like the people of this world,

For no thought is contented.

(Side-bard! - If you’ve never seen it, Ben Whishaw gives a stellar performance as Richard II in The Hollow Crown. Here’s the above monologue. Be forewarned, it’s in a dungeon and he’s pretty haggard. But my lord, his performance is perfect.)

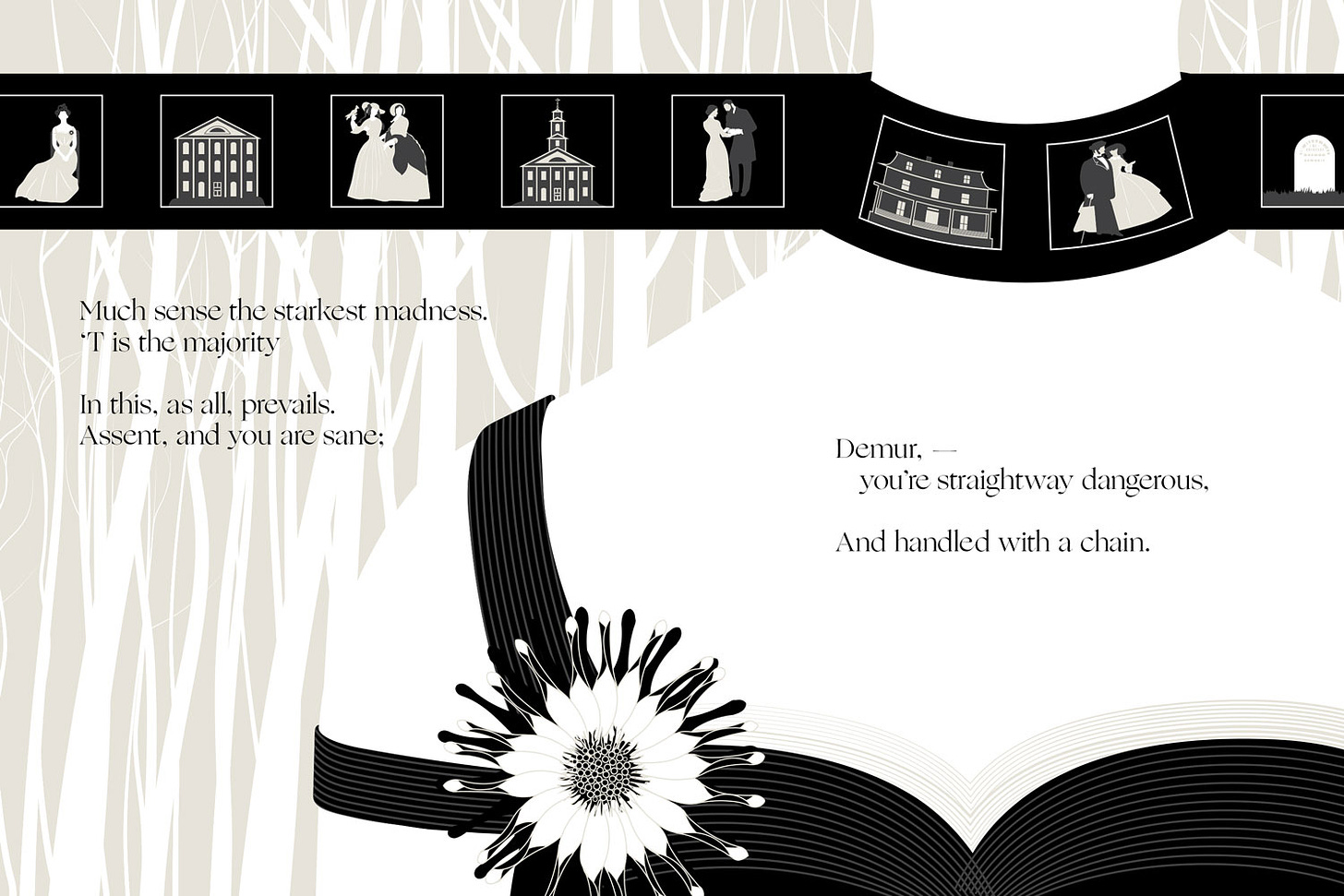

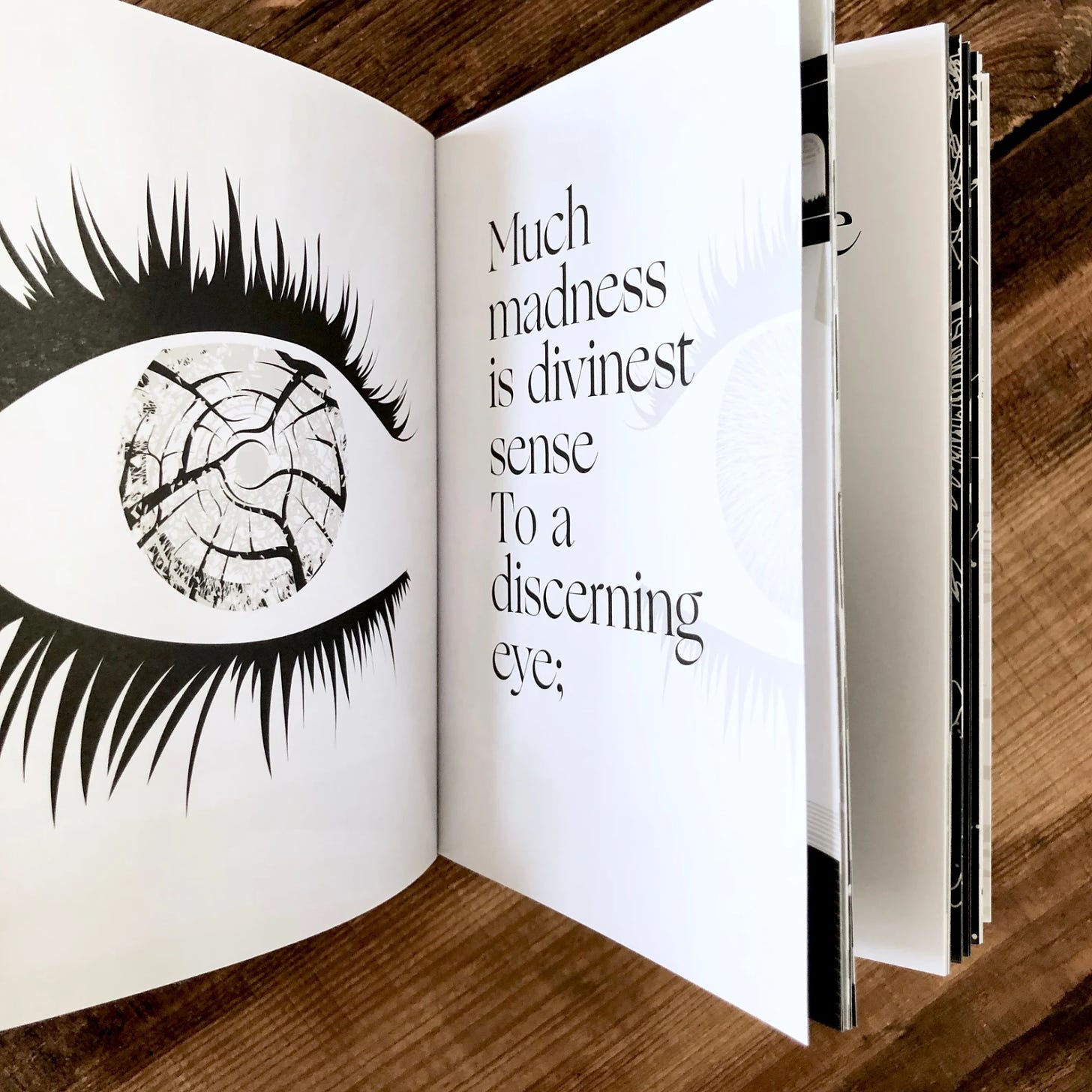

Shakespeare hints at a kind of madness in solitude that, through some magic or strength of will, Dickinson seemed to evade, or at least to survive. There are all of those posthumous diagnoses of her, ranging from depression to agoraphobia. “What kind of a person wants to be alone??” But there’s no denying the courageous and unwavering determination in her writing, so I remain unpersuaded that she was somehow handicapped by her inwardness.

It’s hard to imagine what would happen to a Shakespeare or a Dickinson now. Would he have written sit-coms? Would Emily, rather than writing in solitude, have watched Will’s sit-coms alone in her apartment? I’d like to think not, that great writers must write and would rise above any of our modern distractions and digital opiates. But it is certainly more challenging now than ever to simply be alone with your thoughts.

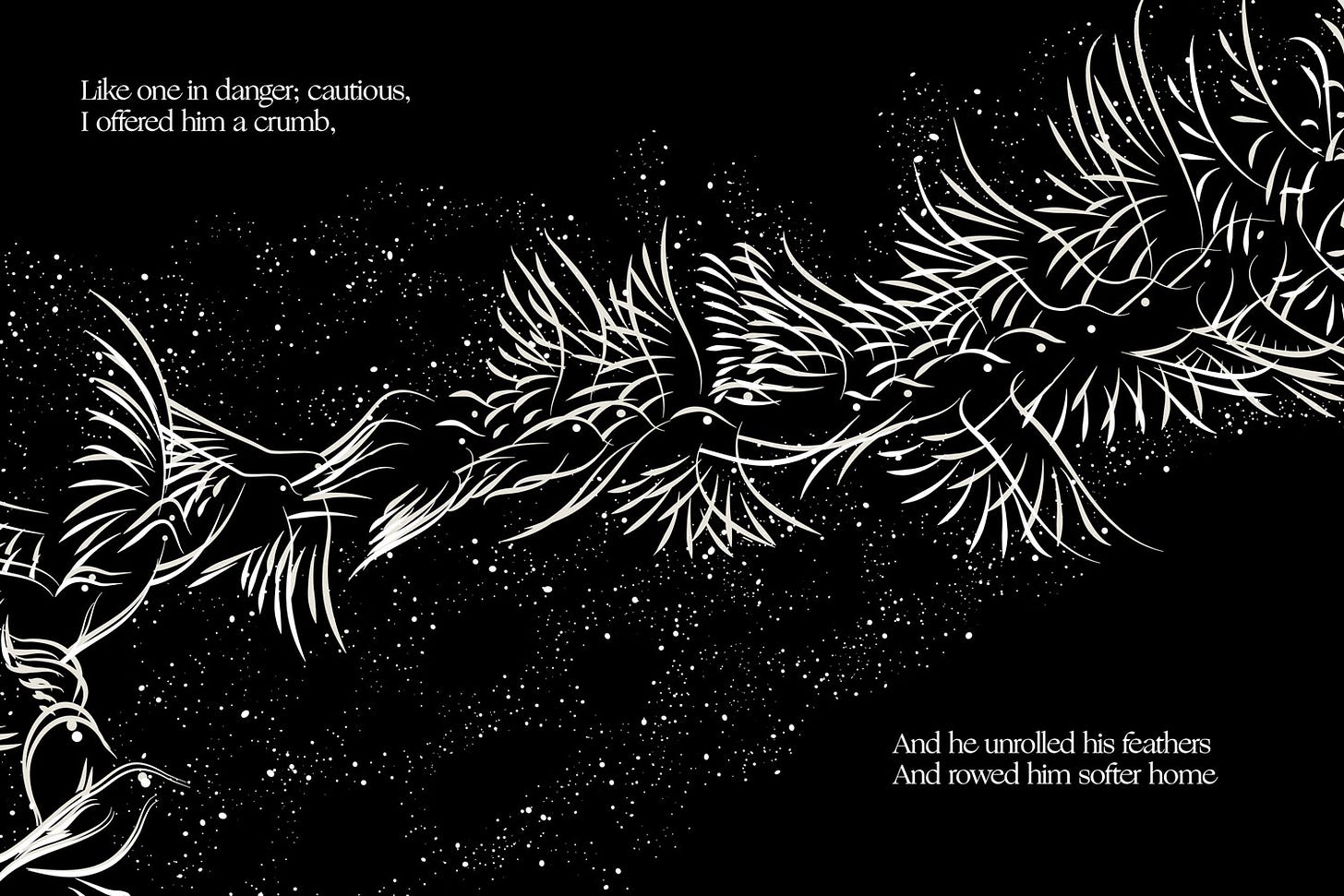

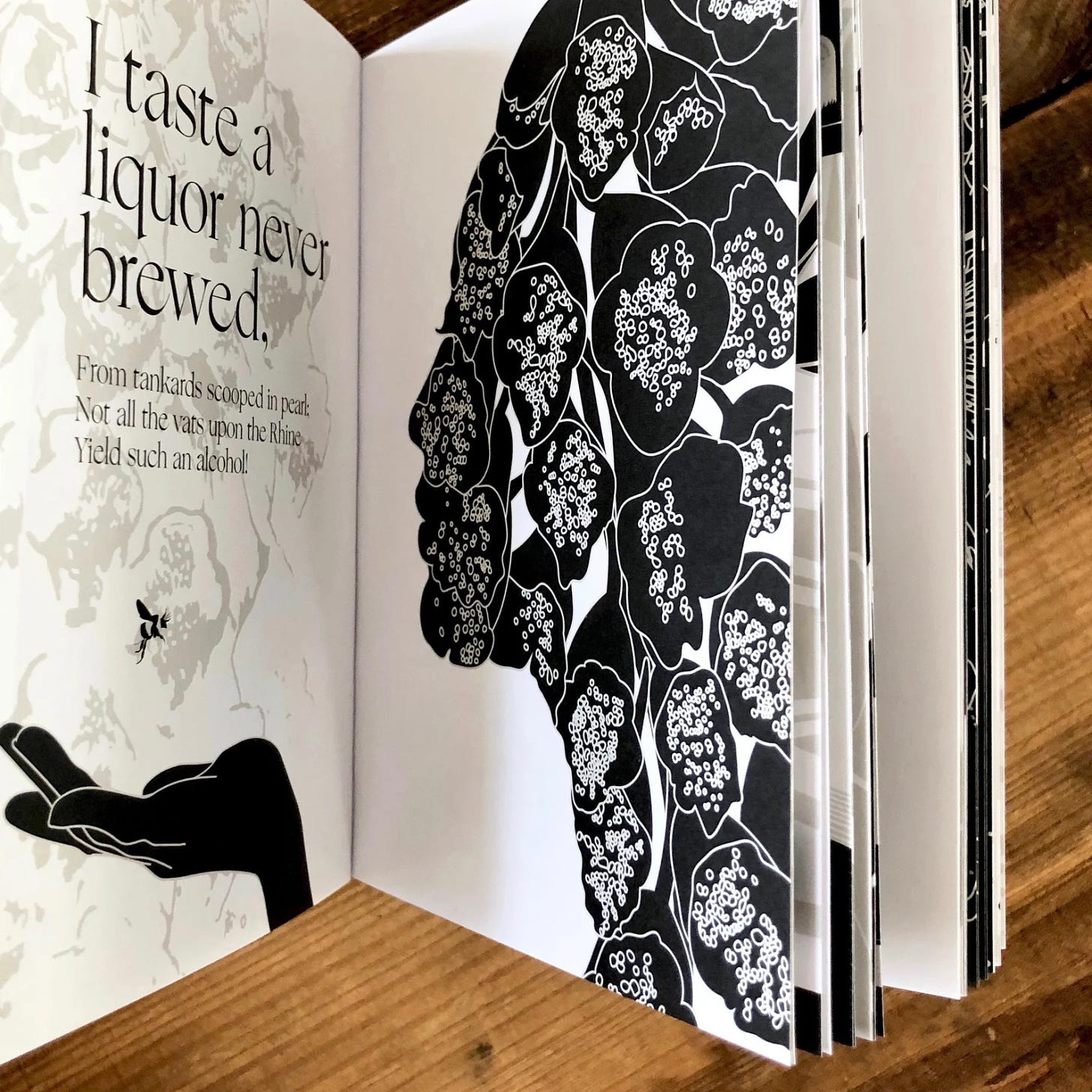

Of course, nature was a kind of companion to her. And I’d imagine that Emily would have pushed back on the declaration that she was alone at all. Her garden and the surrounding landscape were a constant source inspiration for her, and she engaged them with the keenest perception. When selecting and ordering poems for the book, nature was my point of departure. No doubt she was reclusive, but she never collapsed into solipsism. Perhaps she simply preferred the company of a bird to the town gossips?

But like Richard II, her mind shone brightest when wrestling with the mightiest themes. Mortality…Loss...Hope…Truth… these are her domain. And when she expresses her most inward thoughts, you feel that she is simultaneously a dear friend, and a fearless observer - the kind of friend that tells you what you need to hear, not what you want to hear.

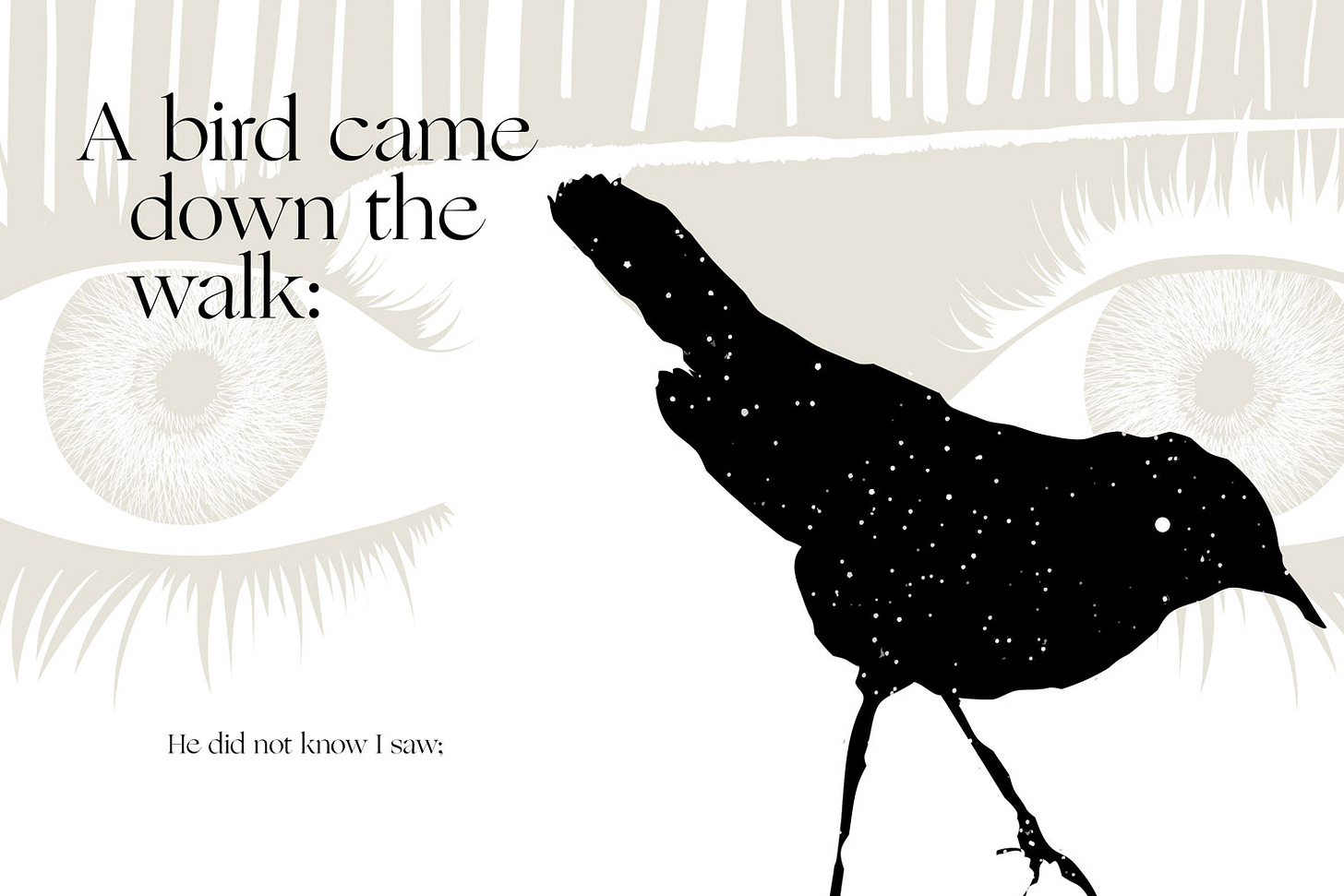

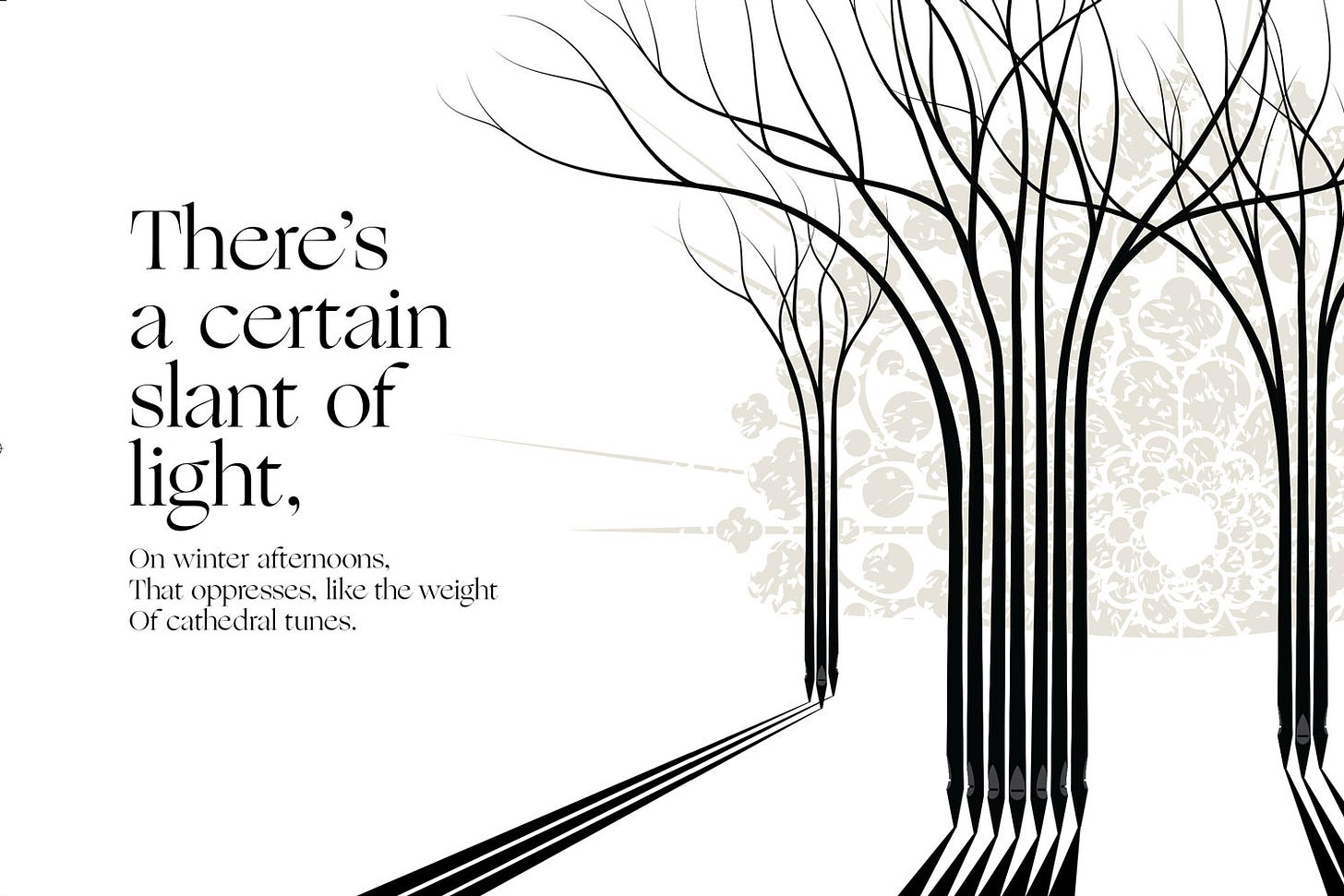

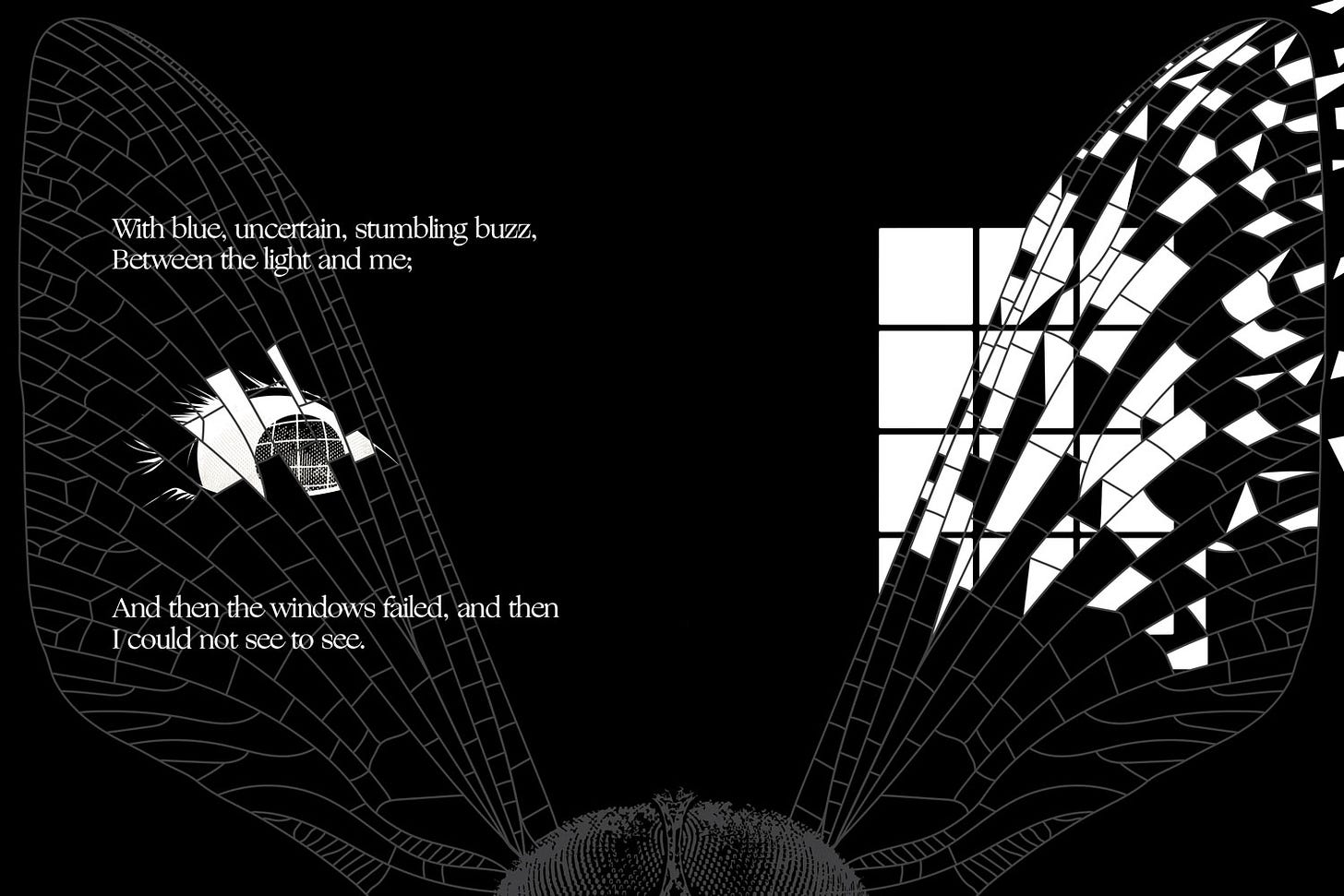

In the book I chose the poems carefully to construct a sort of spirit journey. It begins with her observations of a bird, which lead her to peer deeper and deeper into the nature of herself. She finds an inner world that is richer than the fickle people around her and cuts herself off from the received meaning of the outside world, and must instead make her own sense of things in isolation. She abandons “the bog” - marriage, convention, society - in search of something true.

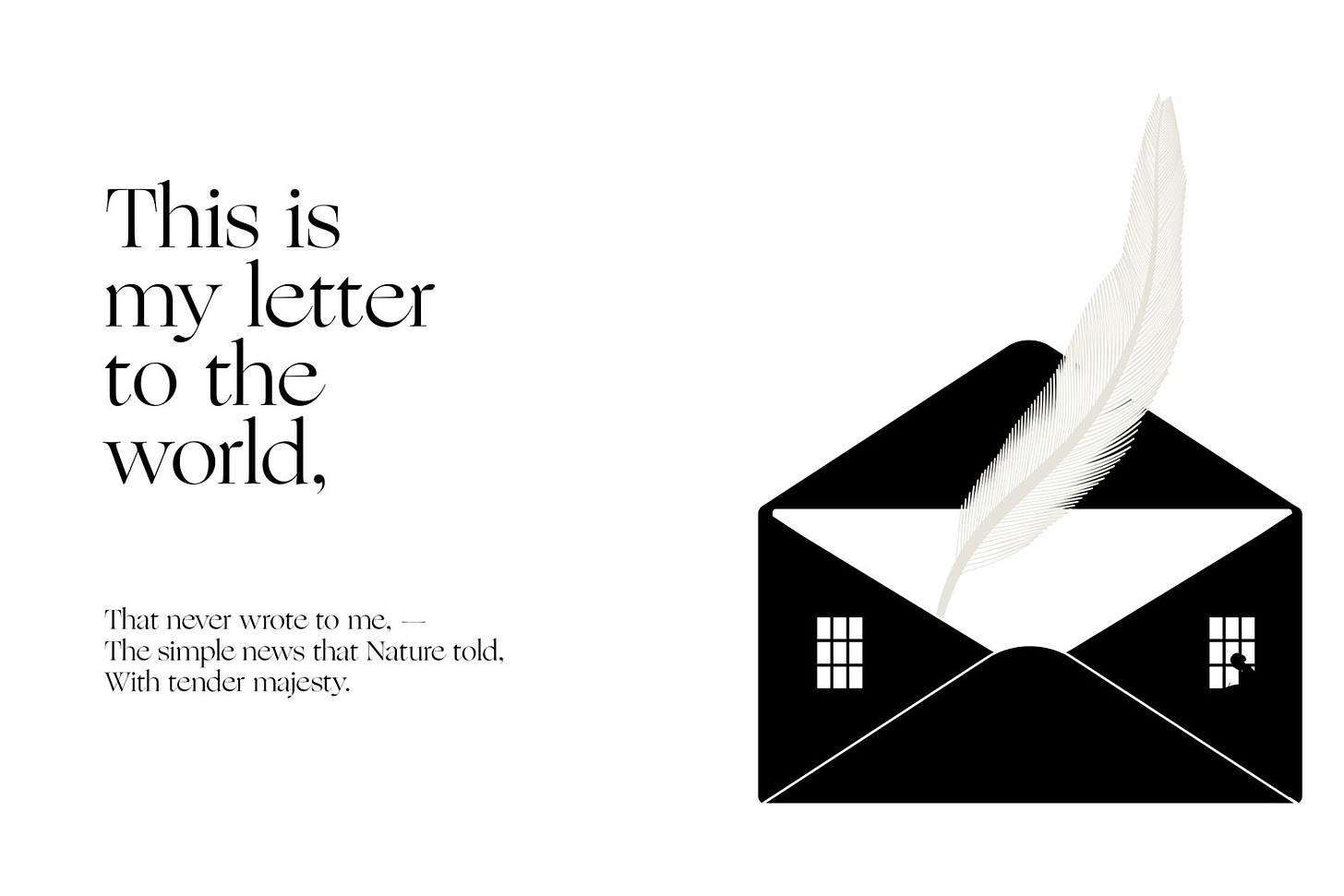

Through solitude, she confronts her own mortality, and it brings her dangerously close to madness. Her redemption is found in writing, communicating what she feels and sees, and transforming that into something beautiful and hopeful.

In the end, because she has no one who can understand what she experiences, she becomes both the speaker and the listener in a closed loop, a “finite infinity” that sustains her and gives her meaning.

I’m sure you can tell that Dickinson is an inspiration to me. As a modern person juggling family, work and community, I marvel at how intensely focused she lived. She sacrificed so much to make room for her singular self-examination. I’d imagine there were times there where she questioned it (and then wrote about her questioning it!). But as impossible as her path must have felt, I am sure that she simply thought too well to be able to talk herself out of it. With a mind like hers, no other companion would do. Who else could have kept up with Emily, but Emily?

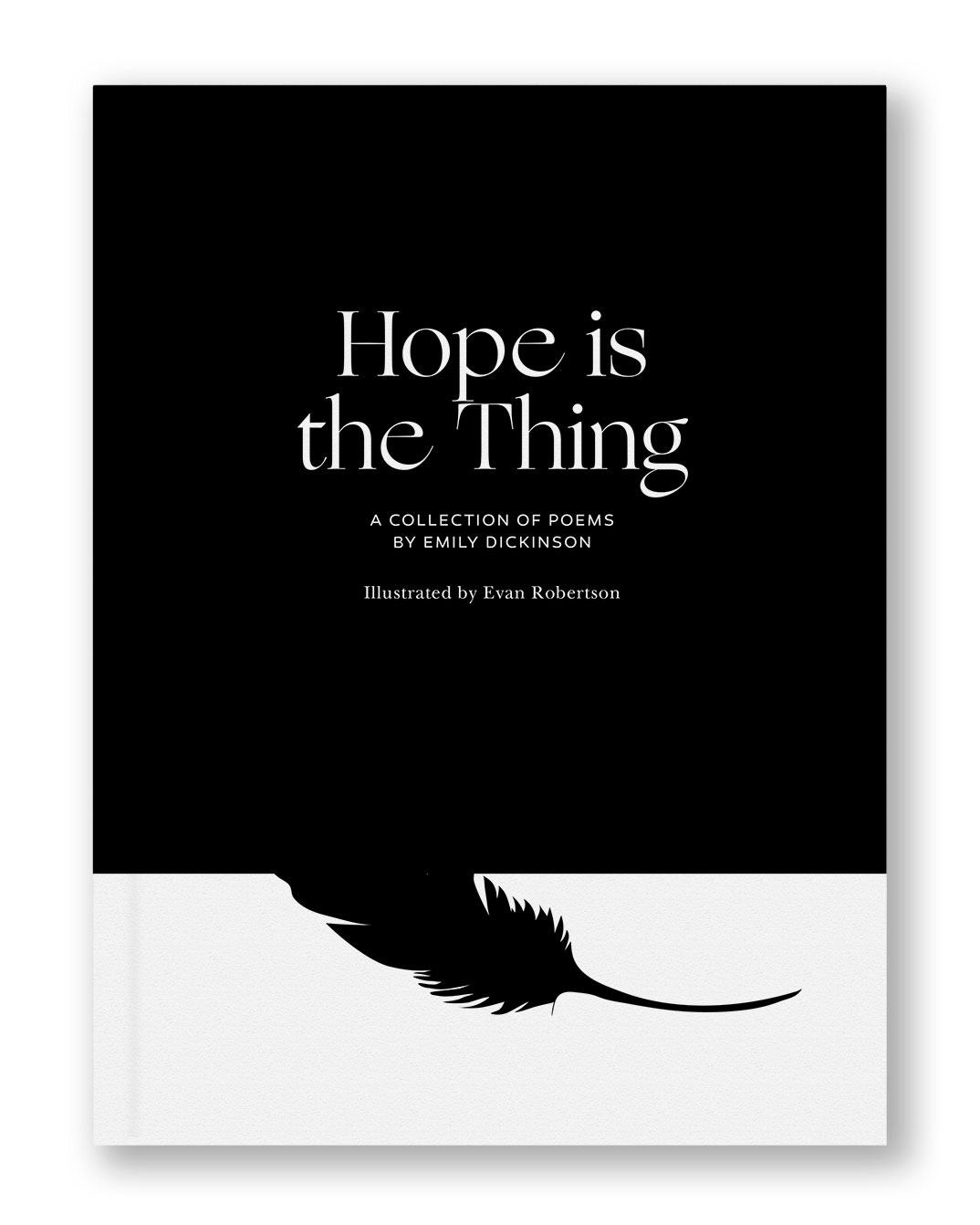

All of the above illustrations and many more are from the book “Hope is the Thing,” an illustrated collection of poetry by Emily Dickinson. It is available for purchase here.