Dickinson on the Virtues of Despair

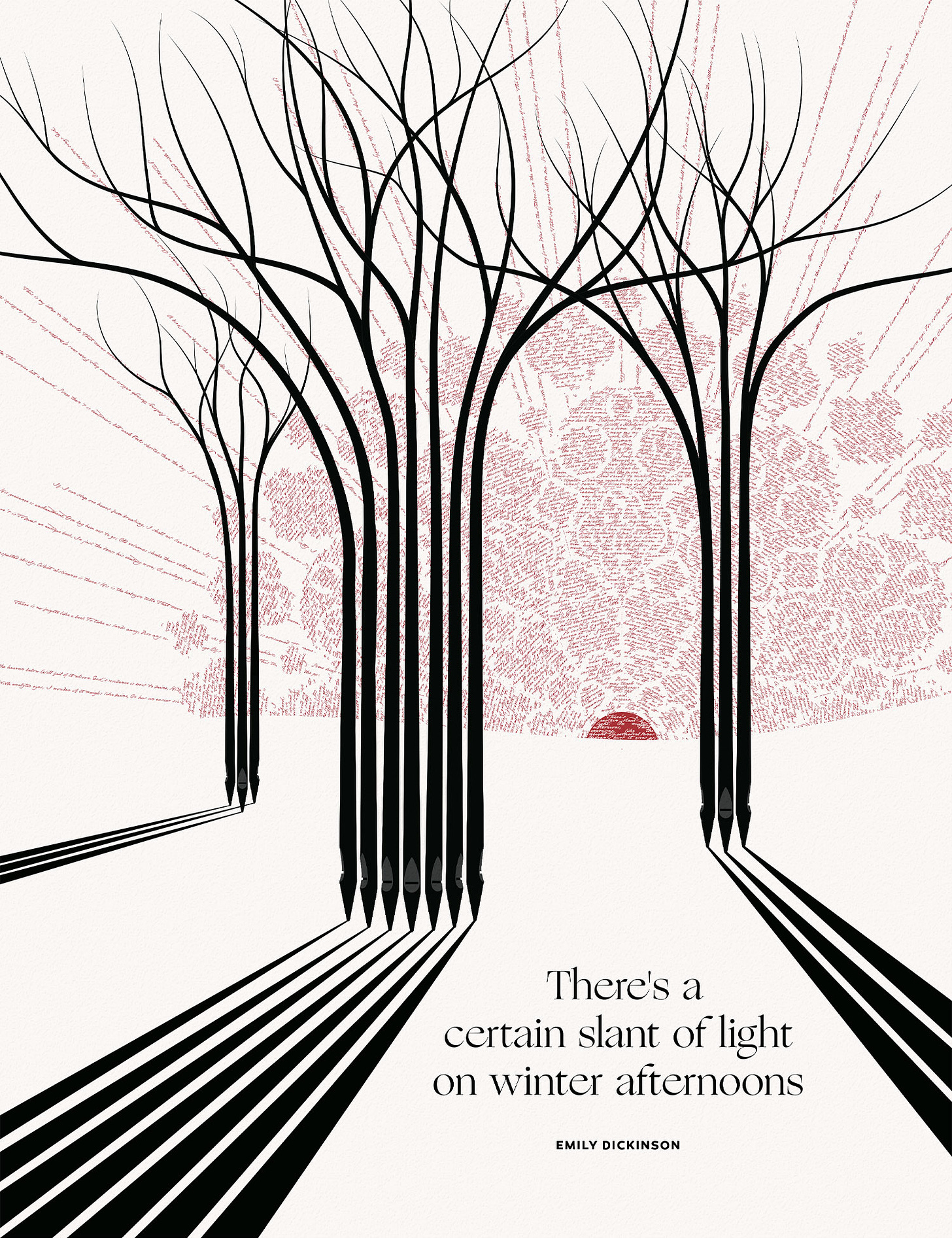

“There’s a certain slant of light on winter afternoons" - Emily Dickinson

As I sit down to write this, we are having our first snow flurry of the season. It’s not winter yet, of course, but the bare trees and stark, harsh light has arrived, and I am greeting it with a fire and an open copy of Dickinson. She was the first poet I really took to as a young man, and I feel grateful to get to tell that story. My first concert was Bon Jovi, my first kiss was at a screening of Crocodile Dundee, and my first car was a Honda CRX. Compared to Dickinson, none of those firsts have aged particularly well.

But Dickinson just gets better with age. Her famously rigid meter and rhyme scheme, which had originally seemed quaint and almost silly to me, now strikes me as an essential constraint borrowed from the religious hymnal traditions she would brilliantly critique. Unlike, say, Whitman, who dispensed with rhyme and meter almost entirely, Dickinson’s work is sharpened by it, focused like a laser beam on her ubiquitous themes: eternity and death, anguish and irreverence, desire and despair.

As part of a language arts unit on Transcendentalism, it was natural for me to view this poem primarily as a celebration of a certain aspect of nature or of the winter season, as if the impetus for the poem was a particular view from her Main Street window in Amherst. I thought of poets as those who could clever contrivances in everyday things, even better if they could hint at some wisdom and meaning. And maybe on occasion, they got it right, but mostly it was entertainment for fancy smart people. (What can I say, I was 13, you know nothing, and assume that a poetic metaphor, no matter how arbitrary, can be made to sound wise with enough effort. With little life experience, there isn’t too much daylight between “There is a certain slant of light” and “Something in the way she moves.”)

But her subject isn’t blue jays, or falling leaves, or even winter. It’s light. It’s the particular dying light at the end of the day at the end of the year, that oppresses and hurts. There is something about it that, for her, is beyond reasoning with and certainly beyond aestheticizing, it is an irrevocable seal, despair.

The word slant, as in slant-rhyme or her poem “Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” suggests that the light has an hidden meaning, an insidious message beyond merely illuminating. This is to the point where the shadows themselves are holding their breath, in anticipation of what? - the dying of the light? Or the creeping realization of “despair” it brings?

Despair had a particular religious meaning for Dickinson, as it did for the puritan revivalists of her time. It meant “the sin by which a person gives up all hope of salvation or of the means necessary to reach heaven.” (source) She couldn’t bring herself to submit to the zealous dogmatism of her community. And yet, neither was she a nihilist. She saw the divine everywhere, and stood her ground in the face of it. Her “despair” of the religious doctrine of her day was a quiet act of protest and the impetus for a radically individual approach to deeper understanding.

She did so through her abundant, relentless writing, which was in itself the ultimate act of faith. As I sit here surrounded by the trees, the first hint of snow, and the slanted light of the late afternoon, I feel a kinship with her. I can’t begin to express it as brilliantly as she did, but the connection is stronger than ever. I can’t say as much for Slippery When Wet or Paul Hogan. Eventually, the light goes, but Dickinson’s expression of longing remains.

Our holiday sale is ongoing. Save 25% in the shop with HOLIDAY2023.

There's a certain slant of light,

On winter afternoons,

That oppresses, like the heft

Of cathedral tunes.

Heavenly hurt it gives us;

We can find no scar,

But internal difference

Where the meanings are.

None may teach it anything,

'Tis the seal, despair, —

An imperial affliction

Sent us of the air.

When it comes, the landscape listens,

Shadows hold their breath;

When it goes, 'tis like the distance

On the look of death.

About the Art

“The illustration depicts the stark light of late afternoon, described in its absence through the shadows of trees that sharpen to cathedral pipes. The sunlight behind her takes the form of a rose window, made up of a collection of Dickinson’s own poetry.”

Art by Evan Robertson. All rights reserved.